Nature Morte

at Baader-MeinhofJune 10th - July 8th, 2022

1322 S 6th St Omaha, NE 68108

Press Release:

Benjamin Langford’s photographs tremble with ecstatic intricacy - detailed enough to overwhelm yet tempered by compositions staid and still. At turns both unremarkably familiar and breathtakingly theatrical, they toe the slippery threshold between the sublime and the mundane. The scenes lie in a third state, precariously animated with all the warmth of the newly dead, petrified by the cold, hollow breath of the barely living. This mortal fixation, both of photography’s life in amber and the dialectical space of still life painting, is reflected in the distanced gaze of Langford’s images.

In “Snow Day (Prospect Park)” we find the joy and romance of the ideal snow day, complete with towering, transcendent clouds. The trees’ barren, lifeless limbs extend while a listless, wandering lot delectate amidst a winter wonderland. Within this frozen snowscape lies the truth of such a passing idyll: the familiar rush of excitement to be free of school, of work, of responsibility, the chance to rend a snowman from ground of white. Its majestic, painterly visage is imbued with a sense of history, a lineage of affection and shared social community: we have seen this sight before on countless museum walls, on postcards and in-mail promotional calendars. The innate, understood feeling the image evokes is inextricable from the commonness of its reproduction and yet no less meaningful for its incessant dispersion.

The hallucinatory optic field of “Spring” signals both a turning of the season and a perceptual shift from distant observer to the more immediate vantage of a passerby on an afternoon stroll. Still-green buds crashing like an Impressionist painting upon the rippled mirror lake blur one’s spatial reason. Behind this cloak of flowers-in-becoming, a fallen tree branch, desiccated yet ripe with moss, rises from the water. Ascending like Lazarus from within the dappled plane of swirling foliage, the photograph appears as interested with the arrival of new life as it is concerned with the persistence of dead matter.

In contrast to the exuberant, first-person perspective of “Spring’s” mis-en-scene, the stoic rigor of “Japanese Garden (Montréal)” frames a detached, analytic space of quiet reverie. A family finds pause for reflection as a young boy stands aloft a rock, chasing his image in an artificial pond. The Stade Olympique, former home to the 1976 Olympic Games, juts into the sky, a modernist shell conceived for a temporary spectacle. One wonders if the impetus for such a grand and immediately obsolete superstructure is related to our seeming need to fashion endless monuments to Nature. Building meticulous sanctuaries for the preservation of the natural splendor beyond is perhaps as much to satisfy our wanton longing as it is an effort to rectify our lack of access, our inability to appreciate an untouched world. We build architectures to grant us permission to return, craft images to serve as polished guides.

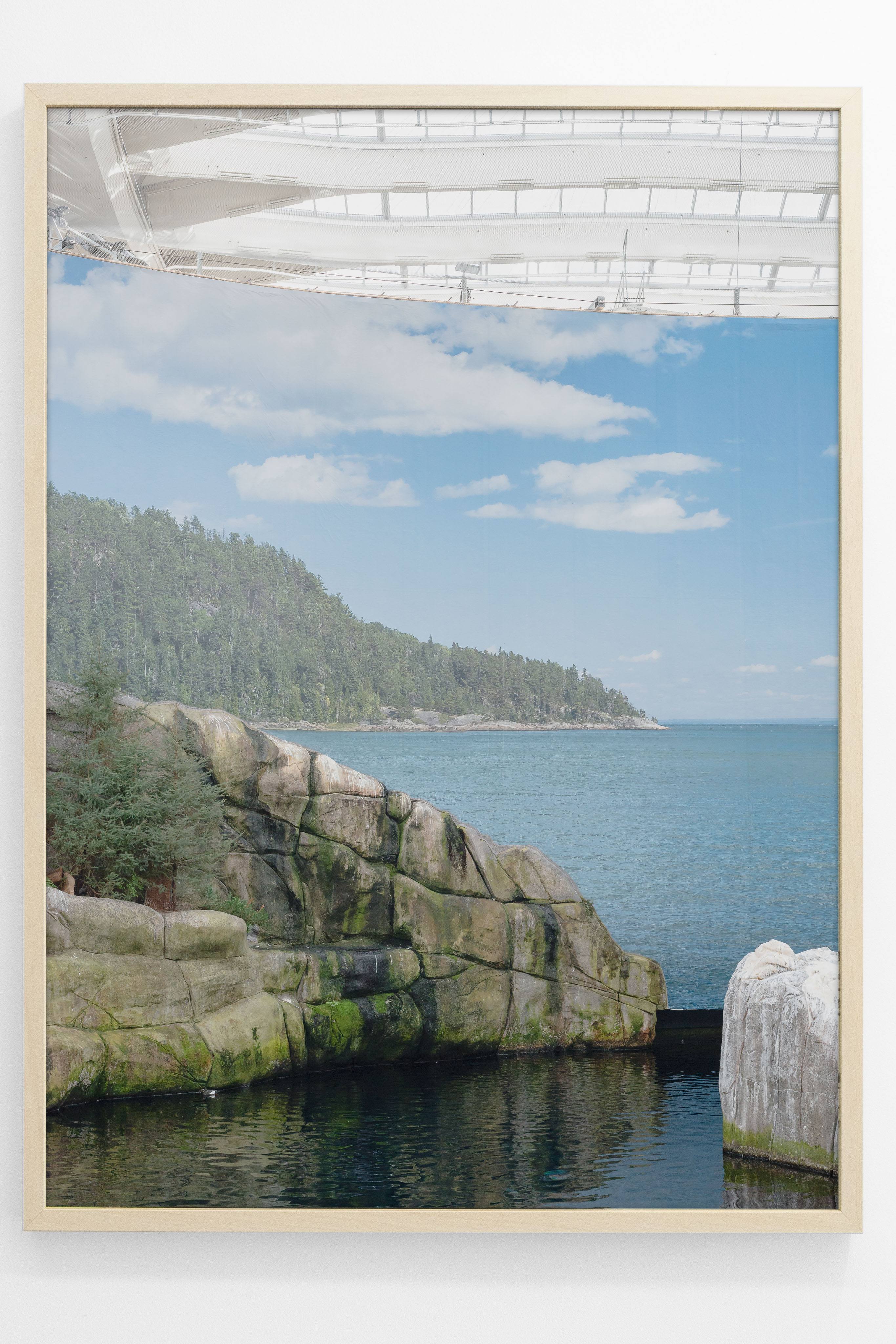

Photographs have an uncanny capacity to unsheathe our idealizations and to reveal representation’s infringement upon the real. In both “Seascape” and “Yose-Ue (Forest Style)” we find our collective desire for the spectacle of illusion on view in complimentary fashion. In the former, there is a Truman Show of sublime theatre. A life-size rocky tableau sits before a monumental landscape photograph, lending credibility to the illusion while highlighting the material limitations of its fantasy. In the latter we find a modest bonsai tree photographed dramatically, as though in nature. Only the muted, geometric shadows in the back- ground dim the lights on this diminutive stage.

Bonsai is an art of self-aware seduction. We know their lives are meticulously rendered with sinewy branches and gnarled, gravity-arched forms bent, twisted, lashed and pulled, bound by the will of a patient aesthete. The fastidious craft is the line, their charming aura of reality the lure. The catch, however, is the space such tiny triumphs conjure, the opening for an appreciation of just such a tree when found in the wild, a proxy to reapproach beauty beyond our willful imaginings. The title “Yose-Ue (Forest Style)” seems to say it all: we are searching for the ideal of the forest through the representation of the trees. In Nature Morte, the world we lost and the one we built to find it coalesce, a roiling ouroboros, twirling photographic petals falling to the familiar lilt of seasons past.